AI Companions for Crew Wellbeing: What CIMON Really Teaches

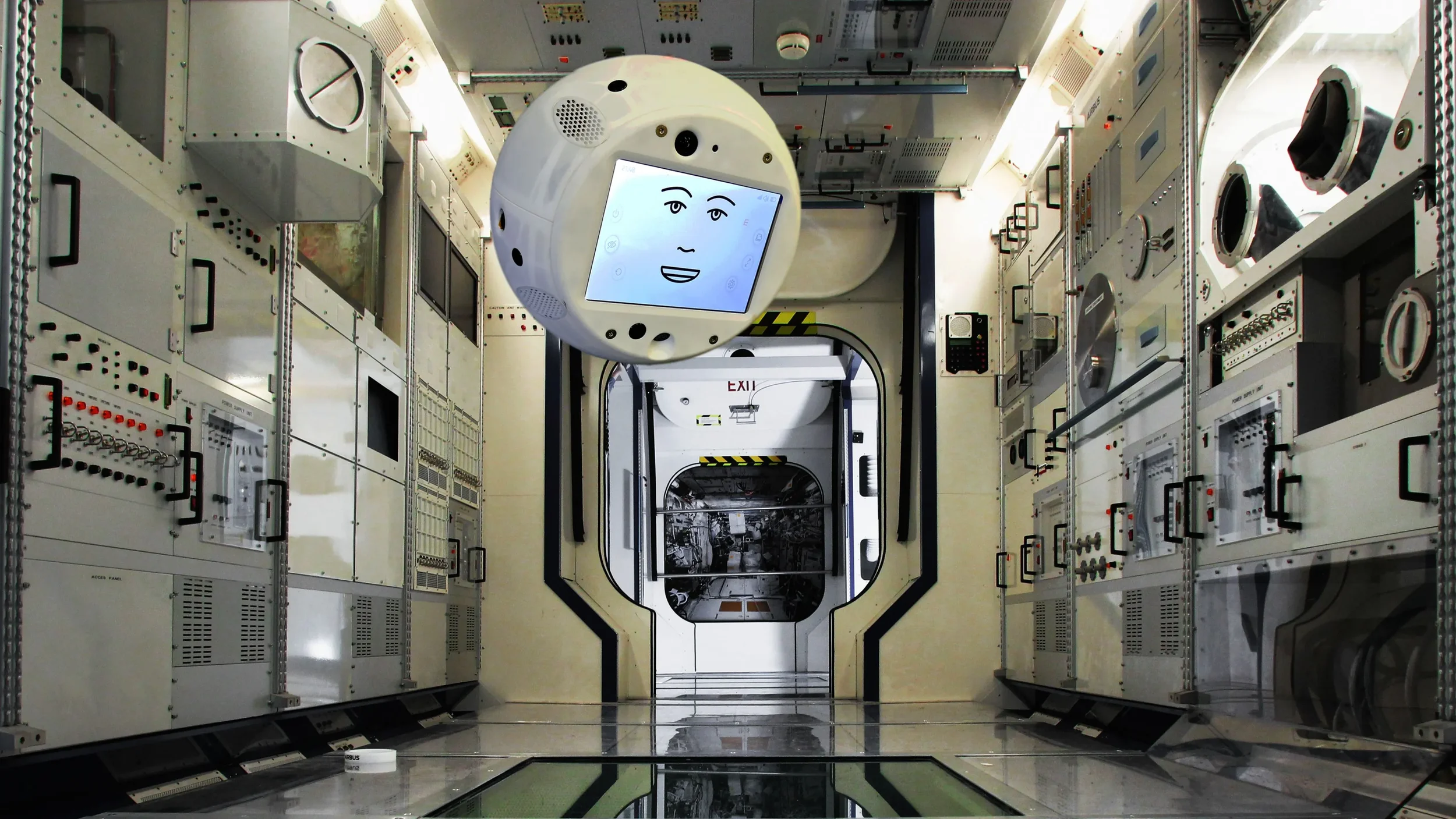

CIMON was designed as a floating, robotic AI assistant for astronauts to walk them through certain tasks and help reduce cognitive overload during space missions.

Credit: Airbus/DLR/IBM

Reducing cognitive load and social stress in orbit—one voice prompt at a time

Long missions compress people and problems into tight spaces. Checklists grow long; comms lag; small frictions escalate. The ISS has quietly fielded an answer: AI assistants that can fetch procedures, record and retrieve notes, and even act as a social buffer. The best-known example is CIMON—a free-flying, voice-controlled sphere developed by Airbus and IBM with the German Aerospace Center (DLR). CIMON is an acronym for Crew Interactive MObile companioN.

CIMON’s second-generation unit (CIMON-2) demonstrated autonomous navigation to named locations in the Columbus module, voice-controlled tasking, and hands-free support for experiments. In other words, it didn’t just chat; it moved itself to where it needed to be, on command, and helped crews execute work. DLR and Airbus reported that CIMON-2 executed verbal wayfinding and task lists reliably, establishing that a floating assistant could be more than a novelty. IBM, for its part, emphasised the research goal of studying how such agents might help with stress and isolation over long missions.

Why does this matter commercially? Because crew time is the scarcest resource in space. An assistant that reduces cognitive load—by keeping the right step visible, logging anomalies in the moment, and retrieving context hands-free—multiplies output without hiring. The analogue on Earth is a theatre nurse who never tires of repeating the next step and has perfect recall. As systems like Astrobee and CIMON co-exist, you can imagine division of labour: one moves tools, the other manages procedures and context. NASA documents have already framed behavioural health and performance (HFBP) as a risk area for exploration; AI aids that partially buffer social stress while speeding tasks are responding to a defined programme need.

Go-to-market positioning that lands is assistive, not anthropomorphic. Sell procedural help, documentation capture, and hands-free retrieval with clear SLAs on speech recognition accuracy, on-board processing (for privacy), and failure modes (e.g., a manual “mute” and safe-dock command). For agencies and commercial station operators, make the case that an AI assistant is a workstation appliance with a voice interface, not a personality. The social benefits then become a measured bonus: reduced friction in crew interactions and a companion presence that some astronauts may find reassuring.

Risks are real and manageable. Voice assistants can mishear; free-flyers can drift; emotion-sensing features invite scrutiny. Address them with bounded autonomy (no free flight during certain operations), on-board processing with opt-in data sharing, and ethics by design—transparent logs of interactions and clear controls for when and how data leaves the station. Ground the pitch in documented trials rather than promises, with a roadmap that’s about reliability before new tricks.

The broader arc is simple: as missions lengthen and crews shrink, intelligent assistants become force multipliers. CIMON proved that an AI helper can navigate, listen and help without getting in the way. The value isn’t that it tells jokes; it’s that it helps humans focus—which may be the most important behavioural health intervention of all.