Why Lunar Governance Needs a Neutral, Commons-Based System — Not Earth’s Politics on Loop

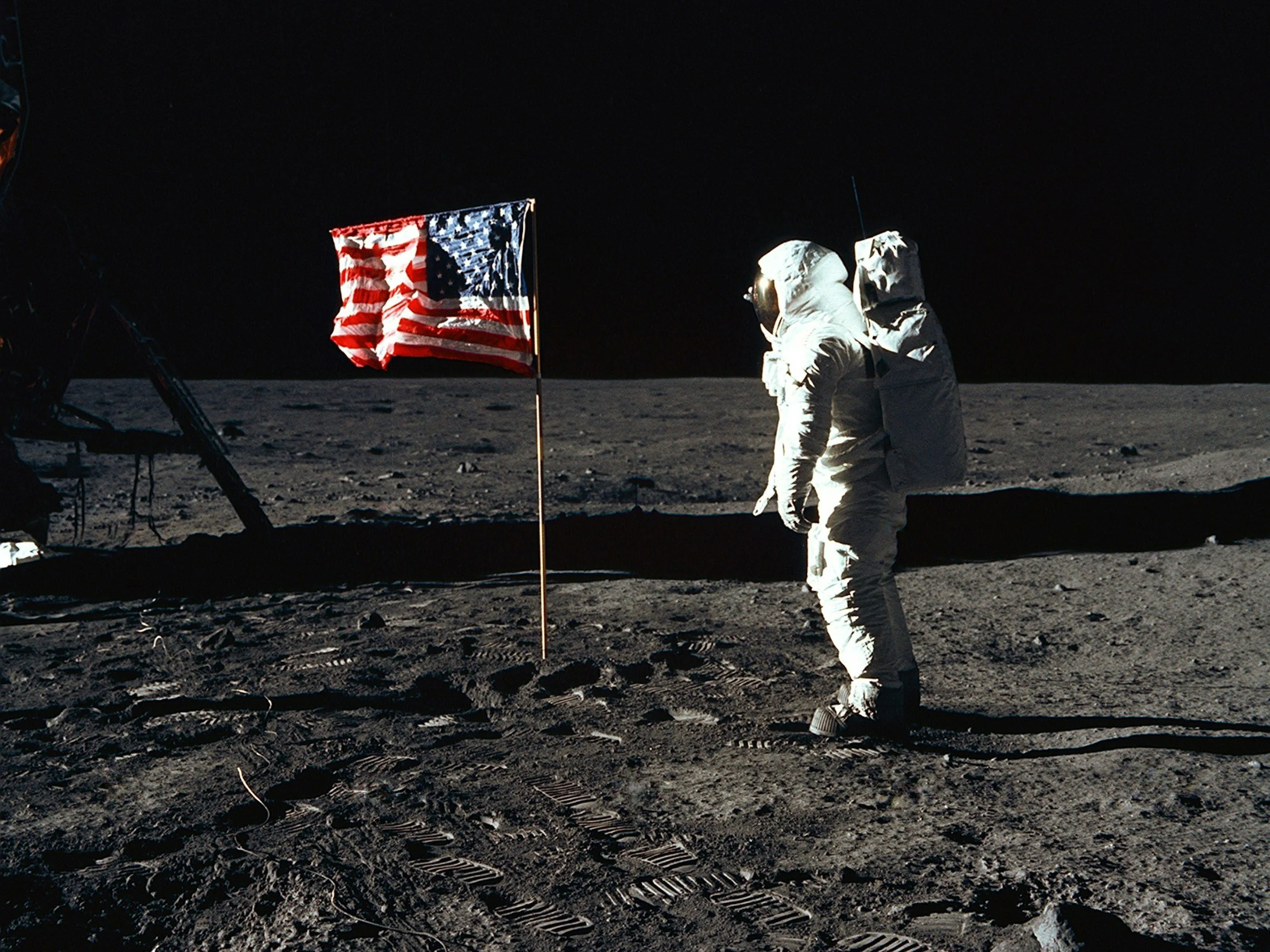

A historic picture of the first lunar landing mission in 1969: astronaut Buzz Aldrin, the second human to walk on the Moon, poses beside the United States flag during Apollo 11’s extravehicular activity at the Sea of Tranquility. Neil Armstrong declared the landing site "Tranquility Base," a permanent designation recognised by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Credit: NASA/Unsplash

Treat the Moon as a commons: a neutral governance blueprint inspired by maritime and Antarctic law to unlock predictable markets

As humanity returns to the Moon, the governance of lunar resources has become a pressing issue. Should nations carve up the lunar surface into spheres of influence, as some propose? Or should the Moon be managed as a commons, akin to the high seas or Antarctica? If terrestrial rivalries spill into space, the risk is clear: conflict will stall development before it can begin. The alternative is to establish a neutral, impartial governance framework to ensure that all benefit equally.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) is the cornerstone of space law. It prohibits national appropriation of celestial bodies and declares their use must be for the benefit of all humanity. However, it is silent on the commercial extraction of resources. The 1979 Moon Treaty attempted to close this gap, calling for an “international regime” to govern lunar exploitation, but it failed to attract major spacefaring nations—only 17 states, mostly non-space powers, have ratified it.

The Need for Neutral Governance

Many scholars and institutions argue that the Moon requires a governance model distinct from terrestrial politics. Suggestions include:

A system modelled on the Antarctic Treaty System, which designates Antarctica as a scientific preserve, bans military activity, and manages access by consensus.

A maritime law-style regime treating the Moon as an international commons, with neutral oversight.

Proposals from civil society, such as For All Moonkind, advocating lunar heritage protection under a UNESCO-style framework.

Earth’s politics don’t translate to the Moon and attempting to transplant terrestrial geopolitics into space is dangerous. Lunar resource sites are concentrated—water ice at the poles, for example—which means rival territorial claims could quickly escalate. If disputes between major powers intensify on Earth, carrying them into space risks open conflict. A neutral body—possibly under the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS)—could act as an arbiter, ensuring resource allocation, dispute resolution, and heritage protection are handled impartially.

The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 provides a striking precedent. Despite Cold War tensions, 12 nations agreed to preserve Antarctica for peaceful, scientific purposes, suspending territorial claims. Today, 56 parties manage the continent by consensus, proving that geopolitical rivals can share governance when scientific and humanitarian benefits outweigh short-term gains. A lunar equivalent would give humanity the same chance to preserve a commons for collective benefit.

Commercial Rationale

Neutral governance is not just a moral argument but a commercial one. Investors and businesses prefer stable, predictable regulatory regimes. Neutral oversight reduces the risk of unilateral appropriation that could exclude smaller states or private firms. A commons-based system ensures broader participation, expanding the pool of innovation and capital.

For industry, investors, and governments, the governance question is not abstract—it defines market entry. A fragmented Moon carved into “zones” raises barriers, multiplies costs, and deters capital. By contrast, a neutral, commons-based framework lowers friction, broadens participation, and allows infrastructure—power stations, logistics hubs, mining ventures—to be financed and shared across borders. The GTM pathway for lunar commerce will therefore hinge not only on technology, but on governance choices that determine whether capital sees the Moon as a contested frontier or as a scalable, repeatable platform. The economics are clear: neutrality isn’t altruism, it’s the condition for market formation.

Conclusion

The Moon is too important to become a geopolitical chessboard. Without neutral governance, disputes over lunar resources will replicate the inefficiencies of terrestrial conflict. With it, humanity can harness the Moon’s potential—water for fuel, regolith for construction, and solar power for settlements—in a way that benefits all. Just as the seas are governed for navigation and Antarctica for science, the Moon must be governed as a commons, insulated from Earth’s politics.