From Space Dividends to UBI: A Realistic Path via Resource and Energy Royalties

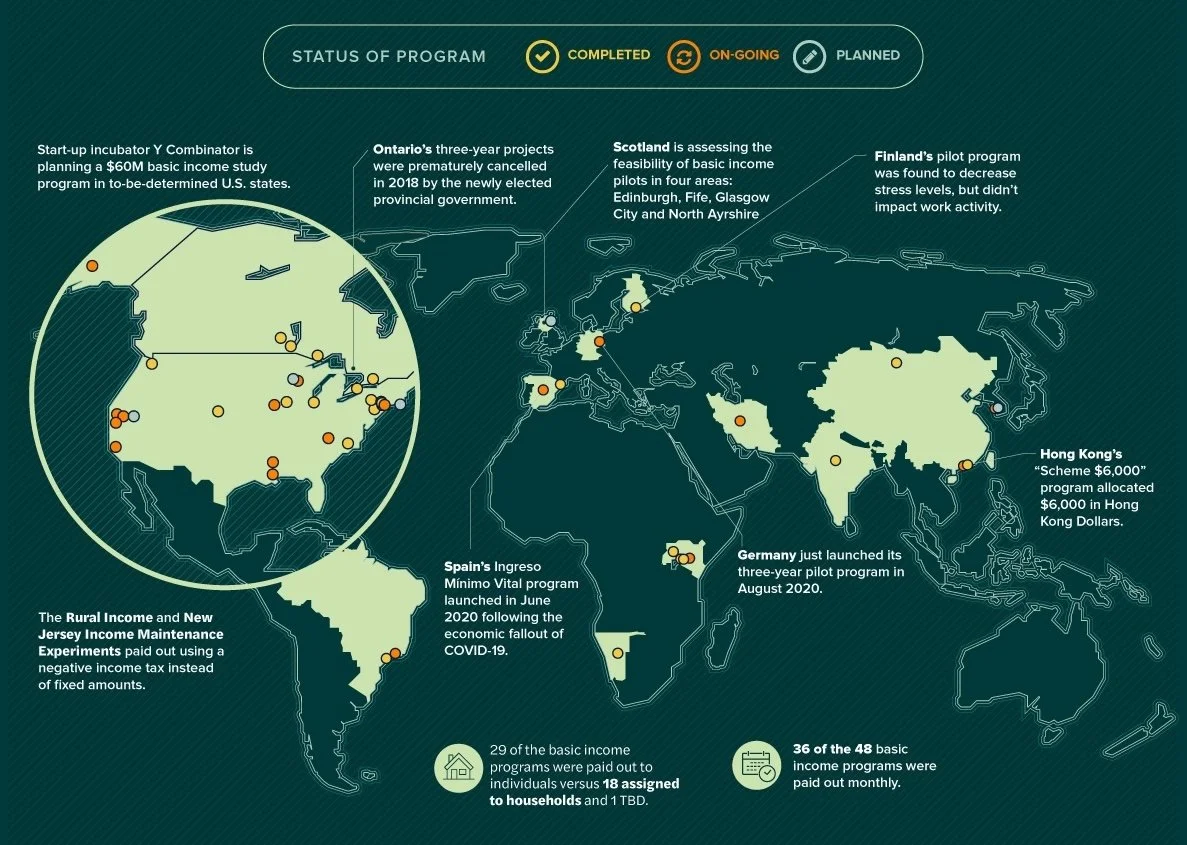

Figure 1. Global map of UBI pilots (as of 2020), compiled from Stanford Basic Income Lab data—evidence that basic income has been tested across multiple regions.

Image credit: Visual Capitalist

Use commons revenues (Alaska- and Norway-style) to seed a universal citizen payout

Figures 1 and 2 map real-world universal basic income (UBI) trials—from Alaska’s long-running dividend model to recent pilots in Europe, Africa, and North America—reminding us that UBI isn’t a theory test; it’s been exercised by various governments at different scales. That context matters here: if societies already trial cash-dividend mechanics on the ground, extending the same payout logic to resource and energy royalties from space is a question of funding source and governance, not social acceptance from scratch. The Visual Capitalist map simply locates those precedents, using data from the Stanford Basic Income Lab, which helps illustrate how a “space dividend” could plug into familiar policy infrastructure.

If high-level UBI sounds utopian, it’s only because we haven’t linked it to the kind of steady, non-distortionary revenue that can actually fund it. Space gives us that chance. As power, spectrum and orbital real estate turn into rent-bearing assets, governments can channel those rents into a citizens’ dividend—much like Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) does with oil royalties, or Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) does with petroleum wealth. The mechanics already work on Earth; the policy task is to move them into orbit.

Start with the precedents. Alaska’s PFD has, since the early 1980s, paid residents an annual cash share sourced from mineral revenues; the state’s Department of Revenue and the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation set out the programme’s history, legal basis and ongoing payment operations in detail. Norway’s GPFG, managed by Norges Bank Investment Management, was created explicitly to convert a finite resource windfall into intergenerational financial income, buffered from political cycles and domestic overheating. These are not theories about redistribution; they are operating systems for transforming commons rents into widely spread household income.

A space equivalent needs credible revenue pipes. Two are near-term plausible. First, a licensing and fee regime on orbital spectrum and scarce orbital resources: the International Telecommunication Union has long documented economic approaches to spectrum pricing, including satellite services, and administrations already collect fees while safeguarding service viability. Second, energy concessions as space-based solar power (SBSP) matures. NASA’s 2024 assessment doesn’t over-promise—it shows SBSP is costlier today, but becomes more competitive if specific capability gaps (in-space assembly, power beaming) close—while ESA’s SOLARIS programme is methodically preparing a decision path for European demonstrations. If orbital power plants generate dispatchable clean electricity for terrestrial grids, royalty streams and concession payments can be structured from day one.

Design matters as much as revenue. A “Space Commons Trust” could embed Outer Space Treaty principles (peaceful use; benefit of all countries) while channelling cash efficiently: ring-fence spectrum fees and SBSP royalties; invest through an arm’s-length fund with transparent mandates; distribute an annual, rules-based dividend to citizens (or residents) on a per-capita basis. Alaska’s codified eligibility and payout rules show how to depoliticise distributions; Norway’s governance demonstrates how to separate investment from day-to-day politics and invest globally to diversify risk.

Is UBI itself workable at scale? The major economics institutions have set out sober frameworks. The IMF’s analytical work clarifies the design trade-offs (coverage, adequacy, financing, interaction with existing transfers), while the World Bank’s guide synthesises evidence from cash transfer programmes and maps where unconditional, universal designs may or may not fit. In other words, we know how to size the dividend against long-run fund returns, phase it in, and avoid crowding out targeted programmes where they remain necessary.

Picture a first step that feels concrete rather than speculative. A regional SBSP pilot earns fixed concession payments plus a sliding royalty on delivered kilowatt-hours; the regulator also auctions standardised “beam corridors” and receiver (rectenna) spectrum, with fees earmarked to the trust. In early years the trust pays an energy rebate (automatically stabilising household bills during shocks); as capacity scales, it transitions to an annual cash dividend—small at first, then meaningful. The legal basis follows existing space law; the revenue logic follows Alaska and Norway; the technology pathway follows NASA’s and ESA’s evolving SBSP roadmaps.

The commercial side must be designed to attract capital while preserving the dividend: long-dated concessions with transparent royalty schedules; performance-linked insurance; open standards for beam safety and settlement so multiple operators can compete on a level field. And because spectrum and orbital slots are limited, auctions should prioritise openness and competition, with fee formulas that avoid throttling service viability—an equilibrium already envisaged in spectrum-pricing guidance.

None of this requires a leap of faith. It requires translating well-understood public-finance tools into a new domain. If we do that, a citizen dividend funded by space commons—first as an energy credit, later as a cash UBI—becomes not a utopia, but an institutional choice.

Figure 2. Timeline of UBI pilots (1960–2020) based on Stanford Basic Income Lab data—from Alaska’s dividend to Iran, Finland, and Kenya—showing that the payout infrastructure already exists, a useful precedent for routing future space resource and energy royalties to citizens.

Image credit: Visual Capitalist