Space Sector Stagnation: Why?

A SpaceX launch at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, United States

Credit: SpaceX, Unsplash

Background

The space sector has shifted from a government-dominated arena to a commercial, globally networked economy. What began in the late 1950s as a geopolitical race is now an ecosystem where private capital, entrepreneurial teams and international supply chains set the pace. By 2021, the Space Foundation estimated the global space economy at roughly half a trillion dollars, with commercial activity driving most of the growth. Launch cadence and satellite deployments have accelerated, while costs have fallen thanks to standardised components, software-led operations and reusable systems. Investors have taken note, with meaningful private and public capital flowing into launch, satellite communications, Earth observation and downstream software markets.

Yet the U.S. government remains a large, anchor customer and funder, directing significant contracts to a small number of well-known firms and startups. That concentration—combined with heavy regulation—raises barriers for new entrants and slows diffusion of innovation across the long tail of commercial users. As Ashlee Vance and others have observed, the Silicon Valley playbook of fast iteration and vertical integration works in space, but it works best when companies can sell widely and fly often.

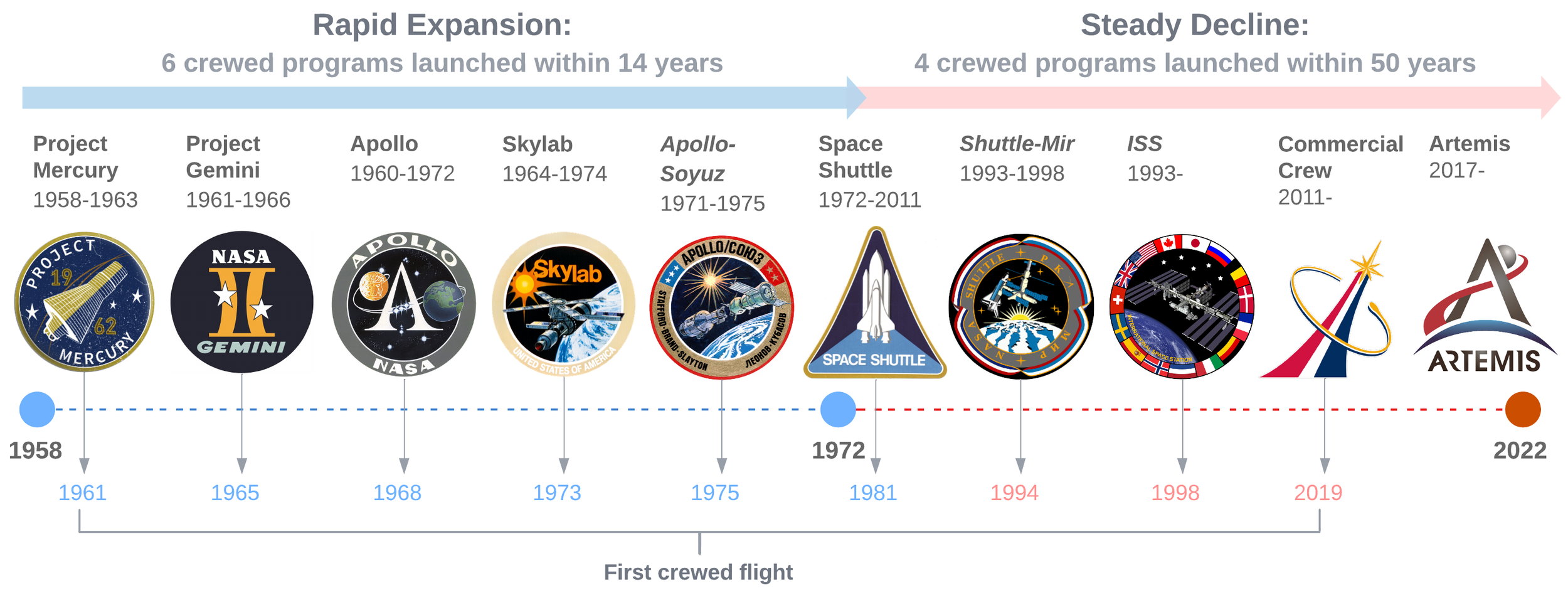

US space programs including international collaborations (1958-2022). The illustration excludes cancelled programs that did not achieve crewed flights.

Credit: Insignias by NASA; Illustration by Sam Puri

Stagnation and High Barriers in the Space Industry

Historical stop–start cycles in public programmes illustrate the risk of bespoke, one-off megaprojects. Atif Ansar and Bent Flyvbjerg document how such endeavours routinely suffer overruns and delays, with each new programme restarting the learning curve. The retirement of the Space Shuttle and subsequent reliance on foreign transport underscored the fragility of project-based approaches. Robert Jacobson notes that budget constraints can push agencies into survival mode, prioritising maintenance over innovation.

Commercially, the result is a high hurdle rate for startups: long development cycles, lumpy revenue tied to a handful of procurements, and regulatory friction that slows time-to-market. Incumbents—Boeing, Airbus, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon—retain scale advantages in certification, contracting and supply chains. The remedy is not more bespoke regulation, but smarter market design: outcome-based procurement that buys services rather than funding custom hardware; streamlined licensing that rewards safety and compliance without stifling cadence; and policies that crowd in private capital by reducing uncertainty. Reusability and platform strategies—exemplified by modern launch vehicles and configurable SmallSat buses—turn space from a sequence of projects into a repeatable product business with improving unit economics.

What Happens if Startups Aren’t Adequately Supported?

Startups are engines of disruptive innovation in Clayton Christensen’s sense: they enter with simpler, cheaper solutions, learn fast with early adopters, and scale into mainstream markets. In space, that means reusable rockets, software-defined satellites, and data services that plug directly into agriculture, energy, insurance and logistics workflows. If capital access, procurement pathways and licensing remain narrow, many promising companies will time out before reaching scale—echoing the industry’s history of casualties like Beal Aerospace, Kistler and others. The opportunity cost is substantial: fewer flights, slower learning curves, higher prices, and downstream sectors deprived of decision-grade data and connectivity.

The commercial answer is clear: broaden demand beyond government by encouraging private-sector service purchasing; prioritise reusability and standardisation to compress cycle times; and maintain light-touch, outcomes-focused rules that protect safety while maximising cadence and competition. The centre of gravity in space is shifting from singular projects to repeatable, learning systems. That’s where durable margins and market expansion will be created.