What Virgin Galactic’s Stumbles Teach About Space-Business Discipline

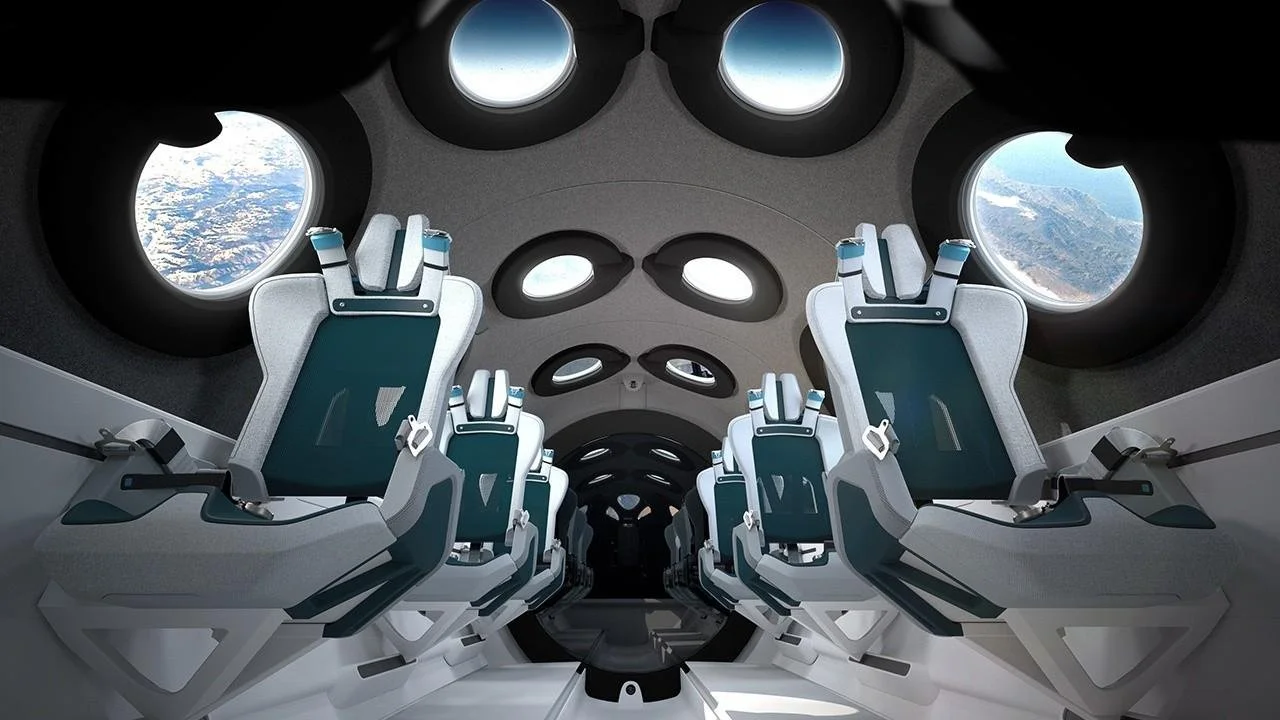

The interior of Virgin Galactic’s VSS Unity spaceplane.

Image credit: Virgin Galactic

Financing the bridge, pacing safety, and scaling before the market runs out of patience

Space companies don’t fail for lack of vision; they fail in the gap between vision and cash flow. Virgin Galactic offers a sharp case study. The firm proved paying passengers could reach suborbital space, yet its programme slid into a long revenue drought, a punishing cost base, and investor fatigue. For boards, CFOs, and programme managers across the sector, the lessons are concrete—and widely applicable.

Begin with safety. In 2014, SpaceShipTwo broke up during a test flight, killing one pilot and injuring the other. The National Transportation Safety Board found that Scaled Composites had not fully engineered against a single human error: the feathering system could be unlocked prematurely, and once unlocked, aerodynamic loads forced an unrecoverable deployment. In the Board’s words, the probable cause was a failure “to consider and protect against the possibility that a single human error could result in a catastrophic hazard.” The consequence was years of redesign, procedure hardening, and regulatory scrutiny. The schedule reset was not measured in months; it was measured in years. Any company planning human flight should assume the same after a serious mishap: independent reviews, simulator and procedure upgrades, and capital buffers that recognise a multi-year delay as a base case, not a tail risk.

Next, define the product generations and finance the bridge between them. For clarity, Gen-1 is the first certified, revenue-earning system; Gen-2 is the higher-throughput successor that improves margins and cadence. Virgin’s Gen-1—VSS Unity plus the VMS Eve carrier—could fly, but with few seats and limited flight rate it could not support a public-company cost structure. Management therefore paused Unity in mid-2024 to concentrate resources on the Delta Class (Gen-2), with test flights planned before commercial service in 2026. Strategically, the logic is sound: scale requires a vehicle designed for cadence. Financially, it created a two-year hole in operating income that had to be bridged with cash on hand or new capital. That is the core lesson: never zero out Gen-1 revenue unless the Gen-2 runway is already funded to first customer delivery and backed by credible schedule risk allowances.

The market’s response to that hole was predictable. Revenue fell to de-minimis levels while quarterly losses continued; headcount reductions followed; and the company executed a reverse stock split as it sought to extend runway to Delta’s debut. Capital markets can price delay; they struggle to price uncertainty when the operating line is near zero. That is not unique to suborbital tourism. Any hardware programme with a pause between generations faces the same test: is there enough balance-sheet stamina—and enough schedule credibility—to cross the gap?

Cadence is where aerospace businesses earn their margins. A flight operation that happens monthly is a demonstration; weekly and then daily operations, with stable turnaround, spares pools, and a disciplined change-control board, are a business. Virgin’s Unity flights showed proof of concept, but the pause removed the few, tangible operating metrics investors could watch—dispatch reliability, aborts per 100 flights, hours between unscheduled maintenance, booked-but-unflown backlog—and replaced them with development milestones. By contrast, a competitor like Blue Origin, after its own grounding, returned New Shepard to service with a published corrective-actions list and resumed flights, restoring a cadence narrative that public markets can understand. The management takeaway is simple: communicate like a regulated utility. Publish the operating scorecard you intend to be judged on, and report against it even when the numbers are unflattering.

Brand power fades against hard numbers. Celebrity sponsorship and charismatic founders can command attention, but they cannot compress a critical path or refinance a schedule slip indefinitely. Sir Richard Branson’s name helped take Virgin Galactic public through a SPAC combination in 2019, but the post-SPAC era prizes evidence over promotion. In today’s market, credibility flows from cadence and safety metrics, not from media moments. The broader industry should heed the point: regardless of the marquee on the hangar, capital gets more expensive when operating proof thins out.

The most practical lesson is how to fund and operate the bridge from Gen-1 to Gen-2 without starving the enterprise. One approach is to keep Gen-1 flying, even at low margin, while ring-fencing a development team for Gen-2 on a well-defined, change-controlled plan. Another is to monetise adjacent capabilities—research flights, payload services, or training contracts—so that the operating organisation maintains discipline, talent, and supplier relationships during the transition. A third is to use structured customer prepayments and milestone-based government contracts to match cash inflows to the most capital-intensive phases of the Gen-2 build. The common thread is continuity: customers, crews, and regulators see the same team delivering, even as the next machine is assembled.

Safety governance must be explicit and repeatable. The NTSB’s SpaceShipTwo report is a reminder that “pilot error” is often a systems-engineering failure in disguise. Design for error-tolerance, automate where human factors are brittle, and force procedural gates that make it physically impossible to enter unsafe states. Build simulator fidelity for rare but lethal conditions; document hazard logs that an independent board can audit; and budget for multi-year oversight after any major incident. This is not only an ethical mandate; it is a financing necessity. Insurers and lenders will discount risk when they see procedures, telemetry, and audits that close the loop between lessons learned and design changes.

Large aerospace incumbents can also learn from the NewSpace playbook to compress timelines and protect cash. Treat programmes as a succession of minimum viable vehicles and operations envelopes rather than monoliths. Freeze configurations for each campaign and refuse mid-cycle redesigns that poison schedule and spares. Push testing upstream with hardware-in-the-loop rigs and subscale flight articles, then publish what you learned and what you changed; transparency buys time. Most importantly, tie leadership incentives to cost per flight, turnaround time, and on-time milestones—metrics that reduce burn as surely as they build trust.

Competition matters because it shapes customer expectations. Blue Origin’s return to flight after FAA-mandated corrective actions demonstrated a repeatable path back from a grounding. The signal to investors and regulators is that disciplined remediation, coupled with candid public reporting, can restore operations and reputation. The comparative lesson for others is not to copy a rival’s vehicle but to match the operational maturity: closed corrective-action plans, complete documentation, and an unambiguous timetable for resuming service.

All of this rolls up to communications. Speak in the language of infrastructure, not memes. If you are between generations, say so plainly, define Gen-1 and Gen-2, and publish a bridge plan with confidence bands. If a serious event occurs, release the findings, the design and procedure changes, and the oversight cadence you will live under. If you are pausing operations, explain what revenue lines remain and how they contribute to runway. Markets can tolerate a long road; they rarely tolerate opacity.

None of these lessons diminishes Virgin Galactic’s technical achievements, and none guarantees failure for those who stumble. They do, however, explain why some companies survive the trough between prototypes and products while others do not. The industry has moved beyond the SPAC era’s appetite for aspiration without evidence. What investors, regulators, and customers now reward is a sequence they can underwrite: a safe Gen-1 that flies often enough to matter; a funded Gen-2 with a schedule sized for reality; a bridge financed by operations, milestones, and disciplined disclosures; and a leadership culture that values cadence over charisma.

For space firms mapping their next five years, that is the actionable template. Design out single-point human errors, measure everything that affects turnaround, keep some cash register ringing while you build the next machine, and report like a utility. Do those things consistently, and you won’t need founder mystique to raise capital; your operations will do it for you.