Ambidexterity for Robotics Vendors: Stop Playing Not-to-Lose

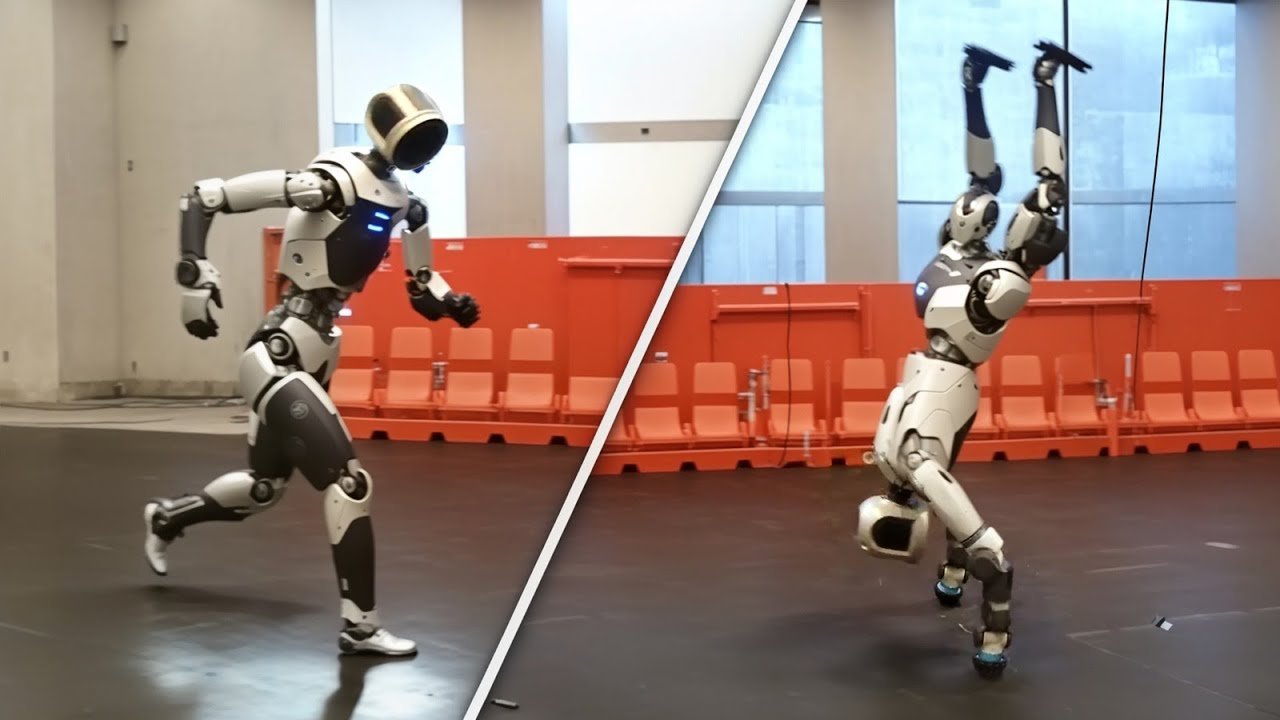

Boston Dynamics have been at the forefront of designing, building, and rigorously testing innovative autonomous robots for over three decades, with a keen eye on what future products may look like.

Credit: Boston Dynamics

Balancing core delivery with bets that make you the category, not a subcontractor

Many robotics firms stumble not on engineering, but on ambidexterity—the ability to successfully innovate today’s products, while simultaneously innovating tomorrow’s solutions. Use cases can become cautionary tales with a constructive core: strong technical talent, multiple platform lines (such as goods-to-person, e-grocery, heavy-lifters, ASRS, etc), yet a Play-Not-To-Lose bias that slows learning cycles and leaves the market open to faster-moving rivals. The remedy isn’t generic innovation; it’s a portfolio and culture reset that turns prototypes into products, and even more critically, products into platforms.

The "Play-Not-To-Lose" (PNTL) and "Play-to-Win" (PTW) concepts were defined by Tony Davila, Marc J. Epstein, and Robert Shelton in the context of innovation strategies, and built on foundational work by Leiffer and McDermott. In the context of robotics companies, it can start with portfolio truth-telling. One platform may reach maturity on its S-curve but take years to prototype compared with earlier leaders in this category. Another platform might be a radical outlier, such as 3D automated storage and retrieval concept traversing ambient, chilled and frozen zones. A third platform might be so flexible that it leverages multiple product spin-offs for different markets. Read together, they show adjacency leverage (software, navigation, fleet control) but also the risk of starving transformational bets while chasing incremental sales. That is the PNTL trap.

Ambidexterity has two layers. Structural—dedicated teams, budgets and KPIs for core, adjacent and transformational work; and contextual—a climate where individuals can make sensible trade-offs without waiting for weekly status updates. Self-analysis and diagnosis may point to brittle processes, leadership misalignment and narrow decision groups that foster groupthink—symptoms that turn radical projects into side quests. The fix is unglamorous: clarify “where to play / how to win,” set a resource split that the company’s leadership can defend (e.g., a deliberate allocation to transformational work), and publish decision rights so platforms don’t compete with each other for resources.

Execution discipline is the multiplier. Treat radical bets like programmes: named product owners; staged kill/scale gates; and a service blueprint from day one (installation, support paths, spares, upgrade cadence). Make POCs fast, bounded and theory-testing, not “free work for the prospect.” When a POC is contract-critical, resource it like the company lives or dies on it, because it might.

Culturally, shift from blame cycles to learning cycles. Fail deliberately and cheaply by documenting and actioning the lessons learned. Bear in mind that the objective of such planned failures is to capture these lessons learned through regular hypothesis testing and in doing so, avoiding catastrophic failures. Publish post-mortems without career death; reward teams for retiring ideas earlier than planned when the data says so. Replace ad hoc feature chases with a roadmap that links to a business model, not just a demo. If business-model innovation lags behind technology, reversing this sequence becomes essential if you want to define, not follow, the market.

Commercially, buyers feel the difference. A PNTL vendor sells concepts and negotiates discounts. A PTW vendor sells availability and validated outcomes—dependable robots, fleet uptime, throughput, calmer shifts—and packages them with integration and support services. Portfolio clarity shows up in proposals: core SKUs for today’s revenue; adjacent options that unlock the next budget; and a well-governed transformational roadmap that smart customers can co-fund. Investors reward that clarity because it produces repeatable gross margin and believable growth stories. The headline is simple, if hard: organise to produce your own luck. Ambidexterity is how.