Planetary Weather Control: Physics, Not Fantasy

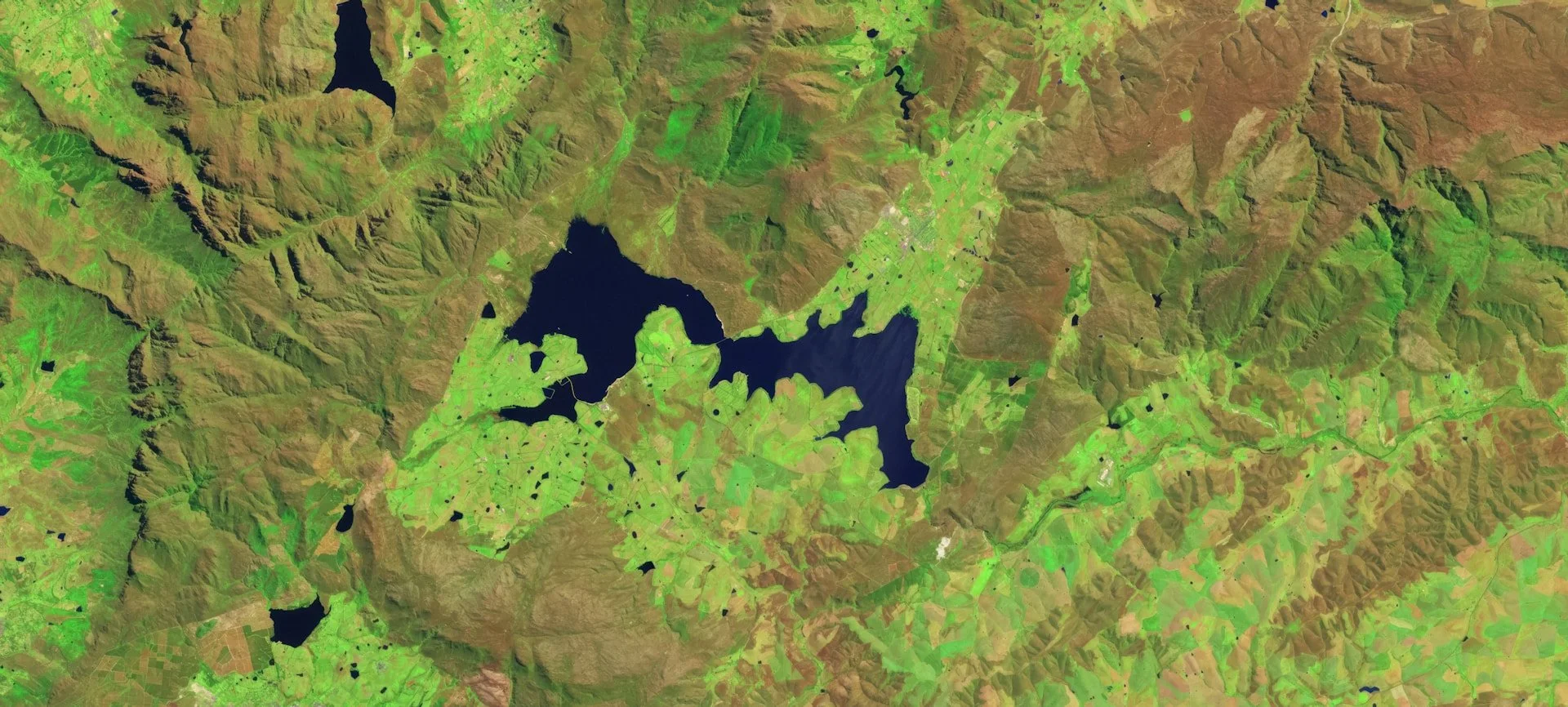

Theewaterskloof Reservoir, Western Cape (Landsat, 2014) — captured before multi-year drought drove levels sharply lower, underscoring why any credible, risk-managed weather modulation would prioritise water security.

Image credit: United States Geological Survey (USGS) on Unsplash

What orbit can—and cannot—deliver, and a sober path from monitoring to limited modulation

Claims about “controlling the weather” surface whenever droughts, heatwaves, or hurricanes strike. A disciplined assessment starts with energy scales, not intentions. Weather is the visible expression of vast heat flows in the oceans and atmosphere; altering those flows at will would demand interventions on planetary scales. Historic field programmes that tried to weaken hurricanes by cloud seeding—most notably Project STORMFURY—ultimately failed for physical reasons: most tropical cyclones lack sufficient supercooled water for seeding to work, and unseeded storms often undergo the same eyewall changes that were once attributed to seeding. The episode is a useful cautionary tale: distinguishing signal from natural variability is hard, and energy constraints dominate.

From orbit, the only credible global lever is radiative control—changing how much solar energy reaches or leaves the planet. Concepts for a space-based sunshade near the Sun–Earth L1 point would reduce incoming sunlight by a small percentage, using either very large membranes or swarms of small flyers to deflect or block light. The physics is straightforward; the engineering and governance are not. Peer-reviewed analyses and classic proposals conclude that such systems are technically conceivable but would require unprecedented industrial effort and multi-trillion-dollar lifecycle costs, with global—not regional—effects. In short: useful for gently cooling the planet, not for ordering rain in one basin next Tuesday.

Most weather-modification ideas operate within the atmosphere, not from space. Here, satellites have a supporting role: targeting interventions, tracking outcomes, and auditing impacts. Cloud seeding can enhance precipitation in some conditions, but results are mixed and highly context-dependent; the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) stresses that there is “no generally accepted evidence” that severe phenomena such as tropical cyclones can be modified. The prudent reading is that seeding is a local, probabilistic nudge—not control—and should be used, if at all, with rigorous attribution methods and public reporting.

Proposals under the banner of solar geoengineering—such as stratospheric aerosol injection, marine cloud brightening and cirrus thinning—aim to reflect more sunlight or let more heat escape to space. The U.S. National Academies recommends a formal research programme with strong governance, precisely because the climate system is coupled: intervening in one place can shift rainfall or heat risks elsewhere. Reviews and recent media coverage of peer-reviewed work on marine cloud brightening emphasise that local benefits (for example, cooling coastal waters) may come with remote downsides as circulation patterns adjust. None of these methods is a replacement for cutting greenhouse-gas emissions; at best they are bounded, reversible modulation options, to be studied transparently and governed internationally.

“Hurricane steering” captures the public imagination but remains non-viable. Beyond the energy hurdle, predictability limits control: small perturbations can propagate through the coupled ocean–atmosphere system in ways that models cannot currently forecast with the precision needed for safe, repeatable operations. The WMO’s position and the retrospective verdict on Stormfury align: there is no robust evidence that tropical cyclones can be reliably weakened or diverted by seeding.

Where orbit does make a material difference today is in observation and attribution, which are prerequisites for any ethically governed intervention. NASA, ESA and partners operate constellations that measure aerosols, clouds, water vapour, soil moisture and terrestrial water storage—inputs that drive weather and hydrology. Instruments such as SMAP (Soil Moisture Active Passive) improve drought monitoring and irrigation planning; GRACE-FO gravity data informs groundwater and soil-moisture outlooks; Sentinel missions under Copernicus provide routine imaging for agriculture and disaster response. These systems do not control weather; they reduce harm by sharpening forecasts, enabling anticipatory action, and giving any trial a transparent audit trail.

If society chose to explore limited modulation, a realistic, governance-first pathway would look like this. First, expand satellite sensing and open data so aerosol–cloud–radiation interactions and regional hydrology are observed at the resolution policy needs. Second, invest in causal attribution—tools that quantify whether an observed change is due to an intervention or natural variability (the lesson from Stormfury). Third, consider small, time-boxed trials under public oversight: for example, targeted cloud seeding in basins with strong prior evidence, or tightly monitored marine cloud brightening pilots to protect vulnerable coral reefs during extreme heat. Fourth, escalate only with evidence and consent, recognising that international bodies are moving to scrutinise these topics in their next assessment cycles.

The benefit lens should be social and environmental, not commercial. In heat emergencies, modest radiative nudges could reduce mortality; in drought, shifting rainfall probabilities over a season could stabilise yields and groundwater recharge; in wildfire-prone regions, targeted cooling could shorten dangerous windows. At the poles, research-grade radiative management might slow melt on specific ice shelves, buying time for emissions cuts and adaptation. Each of these aims frames “control” correctly: risk-reduction within bounds, not command of the sky.

Costs and feasibility vary by lever. Space-based sunshades sit at the extreme—extraordinary capex, multi-decade logistics, and a global governance burden—so any serious discussion belongs in the category of last-resort climate stabilisation, not routine weather making. Atmospheric trials and local seeding are orders of magnitude cheaper in hardware, but expensive in governance: independent monitoring, liability frameworks, and diplomacy to manage cross-border impacts. The cheapest, highest-certainty investment remains Earth-observation capacity and open models, which save lives and improve water management with or without interventions.

Two guardrails should anchor public trust. First, mitigation is non-negotiable: any modulation is a supplement to emissions cuts, not a substitute. Second, rules before scale: the National Academies calls for transparent research with community consent, while the WMO underscores ethical practice and rigorous evaluation; European debates now include whether some methods (for example, space mirrors) should face moratoria pending international agreement. These signals all point in the same direction: proceed, if at all, with humility and verification.

Where this leaves the idea of “planetary control.” Total command of weather is neither scientifically plausible nor societally desirable. What orbit can credibly enable is targeted, auditable modulation to reduce specific risks in specific windows, supported by satellites that see clearly and models that attribute fairly. The prize is fewer disasters and fairer adaptation—achieved with science the public can trust—while the climate-mitigation job carries on at full speed.